Original Research by Upper Wharfedale Field Society. The building survey part of the Study “Grassington and the Great Rebuilding” can be found here and a report in the “Yorkshire Vernacular Buildings Study Group” here

Provided from our Archive by Phyllida.

Digitised and uploaded by Keith P.

There are three things that make man forcefully

To flee from his own house, as Holy writ shows us.

One is a wicked wife, who will not be chastened,

Her man flees from her for fear of her revilings.

If his house becomes uncovered and it rains on his pallet

He seeks and seeks until he can sleep dry,

And when smoke and smother strike his eyesight,

It is worse than his wife and a wet blanket.

Woe is the hall in all times and seasons

Where neither lord or lady likes to linger

Now each rich man has a rule to eat in secret,

In a private parlour, for poor folks comfort,

In a chamber with a chimney, perhaps, and leave the chief assembly,

Which was made for man to have meat and meals in,

And ail to spare to spend what another will spend afterwards.

Vision Of Piers Ploughman 1360-1390

Preface

From a study of the archaeology and history of England we can read about the evolution of village dwellings — from the stone hut circles of the Stone Age, the timber huts and halls of the Dark Ages, the medieval long house with man living cheek by jowl with the animals. The basic single storey timber framed houses with walls of mud and stud or wattle and daub – none of these buildings were durable, they rapidly became what are best described as hovels. But today’s visitors to the smaller towns and villages of England cannot help noticing the large proportion of buildings that date back to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, made of good durable materials which are still in use, suggesting that at this time the tenant farmers and husbandmen had been re-housed in a ‘style that their forebears could never have dreamed of’.

In his excellent book, ‘The Villages of England’ (Thames & Hudson — 1992), Richard Muir reminds us that this change which took place during the period 1570 — 1640, named and identified by Professor W.G Hoskins as ‘The Great Rebuilding’, was based on widespread feelings of confidence in the future that were rooted in the increased prosperity of the period. Richard Muir graphically remarks that new dwellings “erupted like mushrooms in the autumn mists” and in 1550 contemporary observers noted that it was becoming apparent ‘..our buildings, that we have here in England of late days, far more excessive than at any time before.’

Based on a growing affluence which resulted from increasing agricultural prosperity and confidence with a stable Government, new dwellings to replace old inadequate accommodation erupted everywhere, with the pace being set by the South in 1577. It would appear that everybody was interested in what their neighbours were doing, as is shown in the following comment.

‘Everie man almost is a builder and he that hath bought any small parcel of ground, be it ever so little, will not be quiet till he hath pulled downe the old house (if any were there standing) and set a new after his own devise.’

Like today, some people built unsuitable styles and in 1589 an Act was passed in an attempt to regulate the building standards. The requirements of this Act made it mandatory for new cottages to stand in at least 4 acres and with only one family in occupation!

“Mary me thynkesye privye in ye west end and to nere ye logyng, to nere an oven and to nere a lytle larder. I think you had been better to have offendyd yor yey (eye) owtward than yor nose inward.”

House building was a costly affair which consumed many years of savings. In 1670 the cost of building a two storey stone house was about £60, the equivalent of four years earnings of a skilled man. Nevertheless, this remarkable boom in building, ‘The Great Re-Building’, was not confined to the builders of large country houses. It was seen throughout society, going hand in hand with a general improvement in living standards at all levels. The yeomen and the husbandmen were remodelling or building new houses at the same time as the lord in the Hall. The end of the Wars of the Roses meant that it was no longer necessary to build houses that were primarily defensive in character. The great feudal ‘tenants in chief’ were becoming courtiers tied to the Crown by mutual self interest coupled with a change in relationship with their peasants, now working as tenants on their estates, as direct farming of the demesne was becoming less significant and income becoming largely determined by rents. This led, inevitably, to some lands being sold to the tenants, who were not content to remain living in the hovels that were in most cases only marginally better than the beasts’ house. As soon as they had recovered from the buying of their land they took steps to better their domestic comfort by improving the sanitation, heating and light and providing a more private way of life. Inevitably these rebuilt houses became status symbols.

The great majority of these houses were built on existing sites and involved the renewal of old buildings rather than an original construction. The dissolution of the monasteries made a great number of potential building sites available. In addition to the monasteries themselves there were large numbers of monastic manors, granges and other buildings. In this study the Vernacular Buildings Study Group has surveyed and recorded those houses which were rebuilt in the 17th/ 18th centuries. They have also endeavoured to identify the original ‘villein/tenant’ turned freeholder who aspired in many instances to become a ‘yeoman’ — a freeman of England .

Although the dissolution was completed in Henry VIII’s reign, it would appear that many new owners of these monastic properties were superstitious about the sacrilegious implications of using a church for secular purposes. It was not until Elizabeth was well established in her reign that they felt secure. Also it was about this time before they had recovered from the financial burden of purchase. Most of the ruined monastic buildings were used as quarries for ready dressed building stone. Architects, those who plan buildings with a view to aesthetic as well as functional results, as opposed to stonemasons and builders, hardly existed in the 16th century It was the Master Freemason and the Master Carpenter who designed and built the houses. Changing social conditions resulted in changes of design which became influenced by the Renaissance. These ideas of decorative detail originating in Italy and France resulted in the beautiful Gothic styles which are still in use today. This change in design had little effect on the houses built by the yeomen and husbandmen, but where the lord retained a hall and/or manor house in the village, these were often styled in the new fashion.

Today in almost every region of England there are fine examples of Tudor or early Stuart houses and Grassington caught the ‘re-building’ fever too, along with the rest of the county. A look at the vernacular buildings in the area shows that most of them were built in the 17th century and a closer look shows that they were improved in the late 17th to early 18th centuries.

John Wright

Upper Wharfedale Field Society, Vernacular Buildings Study Group

Grassington September 2002

Contents

| . . | Chapter | Links |

|---|---|---|

| The Dark Ages | Click here | |

| The Anglo-Saxons | Click here | |

| The Norman Conquest | Click here | |

| The Middle Ages | Click here | |

| The Manor and the Village in the 12th and 13th centuries | Click here | |

| The Lords of the Manor | Click here | |

| “The Sale of the Century” | Click here | |

| Tenants of the Lord of The Manor | Click here | |

| Building the New House | Click here | |

| Common Surnames in Linton in Craven 16th/17th Centuries | Click here | |

| Acknowledgements | Click here |

The Dark Ages

In pre-historic times the Yorkshire Dales were comparatively highly populated. Ancient house-platforms can be found in large numbers fromvery early (Bronze-age) times to the Celtic and Romano-British periods. Upper Wharfedale contains many examples — Fort Gregory in Grass Wood is a fine example of an early defensive earthwork (Brigantian) and hut circles can also be found nearby. At Lea Green there are fine remains of Old Grassington which was occupied from about 200 BC to the 5th Century AD and became a Romano-British settlement of some importance during Roman times as a grain producing area.

Hut circles

Medieval House Platform Heulagh Swaledale

Lea Green

The first rectangular huts appeared during the Roman occupation of the dale, the bulk of the domestic buildings were hovels made of and earth. The nearest Roman villa was in Gargrave.

By the beginning of the 5th Century, Roman rule had virtually ceased Hadrian’s wall fell victim to a well organised attack by an alliance of Picts, Scots and Saxons in AD36, whilst fully manned. However, the so-called fortified Saxon Shore enabled Britannia Inferior to boom well into the 5th Century whilst Britannia Superior went into rapid decline from the end of the 3rd Century During the latter years of the Roman occupation, the East Coast was repeatedly raided by Angles from the coast of what is now Germany. The Saxons went south. After the Romans left these raiders tended to stay and settle, over-powering the native Celtic Britons (Romano-British).

To the east of Wharfedale was the kingdom of Elmet, near Leeds, which fiercely resisted the raiding Angles, but it was finally overcome in AD616.

The Anglo-Saxons

In the latter years of Roman occupation, Romano-British settlements like Old Grassington started to break up. There was now no market for the grain produced in Upper Wharfedale and by the time the Angles appeared looking for suitable places to settle Old Grassington was probably derelict. In any case, the Anglo-Saxons had a reputation for ignoring the building remains of the previous inhabitants, preferring to do their own thing. Such was the case with Grassington, the occupying Angles selected an area south of the Old Town where there was a good supply of water from a beck, grazing land and timber from Grass wood.

Anglo Saxon timber hut

Anglo-Saxon Hall

The dwellings were laid out on either side of the beck and were built of wood and thatched. The local thegn (roughly equivalent to the Lord of the manor) may have had a more sophisticated house but again built of wood. The Anglo-Saxons came from the forest areas of Germany and were used to timber buildings. The techniques of stone masonry came with the Norman Conquest.

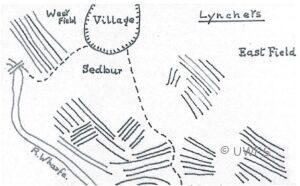

Although the soil was fertile, there were many stones and boulders to be removed before crops could be sown. The new inhabitants developed a technique of collecting all the stone in long lines, about 3 to 4 metres apart and ploughing the soil in between. Because of the sloping land all the furrows had to run the same way and these terraces, a recognisable feature today, are known locally as ‘Raines’, hence Raines Lane, but the text books call them ‘Lynchets’. Thus was born the Grassington of today, a farming community of sheep and cattle.

A sketch map of Lynchetts around Grassington

The Norman Conquest

William the Conqueror took over a country that was fairly well organised socially. Most villages had a thegn who was responsible either to a higher ranking nobleman or to the King. The thegn of Grassington at the time of Domesday was Gamelbar. William parcelled out the country to the Norman barons who had helped him with the conquest and Grassington was given to Nigel de Plumpton. De Plumpton became Lord of the Manor in 1071, holding the manor from the Percey’s, who in turn held it from the King. William had introduced feudalism — only the monarch could own the land and he could take it back. This never happened to Grassington but it did to Linton and Threshfield. The manor was the smallest unit of local government and it was a source of Income for the lord, he reserved the best pasture for himself and his bailiffs or stewards acted on his behalf. In Grassington the lord kept Grass Wood, his part of the manor was known as the demesne. The villeins, as the ordinary folk were called, held strips of arable land and had rights of common pasture and turbary rights for peat from the moor instead of wood from the woods. In return for all this the villeins had to give a stated number of days work on the demesne or as craftsmen, according to their skills. (By the 15th Century, although still tied to work for the lord they began to pay rent and receive wages.)

Another source of income for the lord was the market. Grassington received its charter for a market and a fair in 1282 for which the lord paid £10 to the King. A further source of income for the lord was the mill and bakery. Everyone had to have their grain milled at the ‘soke’ mill and their bread had to be baked in the common bakery. The estimated value of Grassington to the lord in Henry VII’s reign was £30.60p — equal to several thousands of pounds today.

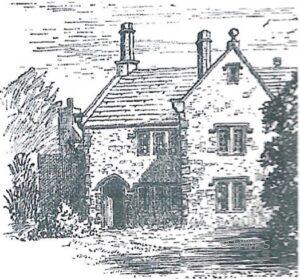

In Grassington the lord made only occasional visits to his Manor House or Hall. Grassington Old Hall, built in the 14th Century, was the first stone building in Grassington and probably stands on the site of the Anglian headman’s timber house erected when the village was first settled. It has been much enlarged since those days. When the hall was not being lived in by the lord, it was rented out. In 1379 when Robert de Plumpton was the lord, the tenant was John de Scardeburg. (See Poll Tax Schedule)

The Old Hall Grassington

Ladywell Cottage

In 1319 Nigel de Plumpton signed a grant to the Abbot of Fountaines Abbey, permitting the movement of sheep along High Lane to the annual sheep fair at Kilnsey.

Another old stone building in similar style to the early part of Grassington Old Hall is Ladywell Cottage. This was probably built as a guest house for one of the Abbeys (either Fountains or Bolton Abbey) as it is on the sheep route to Kilnsey.

The Middle Ages

In the years before the Black Death in 1349, England was primarily an agrarian society. By the 11th Century only about 10% of the population lived in towns. Production was largely agricultural. Late Saxon England was well populated and there is evidence to show that there had been no increase in the amount of arable land since the end of the Roman occupation. Archaeological studies show that the principal crops had been cereals. Barley for brewing and wheat for bread, but rye was not a significant crop. Studies of animal bones show that beef cattle was the principal meat consumed with smaller proportions of pigs and sheep. Sheep were kept for wool production far in excess of contemporary continental practice, showing that Saxon England, like Roman Britain, was a substantial producer of wool and it was upon the export of wool that the wealth of the country was based. (At both rural and urban sites investigated, sheep bone fragments constitute between 25% – 50% of the total.) After the Conquest, wool continued to be the primary source of wealth.

The land belonged to the King who shared it out among the nobles who supported him and they became the ‘tenants in chief’. The farms were worked by the villeins who received no wages other than in kind. Nevertheless, their standard of living, compared with their European contemporaries was very high even though compared with the commercial centres of Italy and The Netherlands they were backward.

Reconstruction of a Medieval House

The reason for this high standard of living was primarily due to the stagnant level of population thanks to frequent outbreaks of the plague. The crunch came when in the early 14th century over one third of the population succumbed to the Black Death. The plague was less severe in rural areas and in Craven it was even less severe than in other parts of Yorkshire. In Grassington the death rate was probably 27%, compared with the rate of 37-42% in places such as York and Pontefract. The result of this catastrophe, whilst improving the over-population problem, was a withdrawal of rural farm labour. Rural workers found that work in urban areas was much more rewarding and there was a great exodus from the countryside to the towns.

In the 12th century, churches were mostly built, owned and endowed by the feudal lords who provided the priest. The churches were supported by tithes which were paid in kind to the Priest or Rector (thus if the owner lost his lands, the church’s income was not affected). Many churches were appropriated by the monasteries and great tithe barns were built to house the tithes which were paid in kind. Some monasteries held the advowsens for several churches and by the Dissolution, out of a total of over 8,800 churches, over 3,000 had been appropriated. It had become a common practice for the nobility to make gifts of land to the great religious houses in exchange for prayers to be said to ‘ease their entry into heaven‘. As most of this land was grazing land for sheep and wool being the basic commodity on which the wealth of the nation was based, the monastic wealth became very great. No wonder that Henry VIII was anxious to get his hands on the church’s property!

In order to manage the sheep, special farms or Granges were established by the monasteries. These were run by lay brothers who were overseen by the monastic Cellarer, who was a canon. In the mid 16th century the annexation of the vast monastic estates by the crown, during the dissolution of the monasteries, came at a time of great social change. Henry had inherited the throne in 1509 to find that the lower orders were getting ‘too big for their boots’. He was alarmed at the slow but sure improvements in conditions. He promptly introduced legislation to keep them in their place particularly with regard to their dress1. In addition there was trouble between tenants and landlords who were enclosing land for their own use and ‘robbing’ the tenants of what they saw as their right to free access to the common pastures. In Giggleswick there were riots against the Cliffords but Grassington seems to have been trouble free.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries and the annexation of the monastic lands by the Crown resulted indirectly in the release of land for sale to the tenants. In effect this was the first time that it was possible to purchase land since the Conquest, when William had introduced the feudal system. Some of the estates were sold to the old families who had supported the Crown in its break with Rome and some to speculators. However, a side effect was that all over England many ordinary tenants now had the opportunity to become freeholders for the first time.

After the Dissolution the lordship of the manor of Grassington was in the hands of the Clifford family. Grassington in the Middle Ages was a place of little importance2. There was no Church, no school, no inn and no resident of any substance. Grassington was part of the ancient Parish of Linton-in-Craven which included the manors of Linton, Threshfield, Grassington and Hebden. The Church of St Michael and All Angels, built by the Thegn in the 10th century lay in the manor of Linton.

In Grassington there were at most only two stone buildings, the Hall and a Manor House for the steward. The other dwellings would have been of timber or possibly cruck, although to date no house in Grassington has been shown to be of cruck frame construction. The walls would have been filled in with mud and stud or lath and plaster. Although some tenants were now being paid in cash rather than in kind, they would have found it difficult to accumulate savings of any great amount. The lord by the 16th century would not have lived in the Hall or Manor House. These were let out to tenants and records show that Thomas Johnson was one of the last tenants in 1564. The Hall was left to Francis Clifford by Lady Anne Clifford in the 1570s.

Interior of late 15thC merchant’s house

George Clifford, Earl of Cumberland from the engraving by Thomas Cockson

When George, 3rd Earl of Cumberland inherited the Manor, a survey was carried out by Samuel Peirse on behalf of the lord. This showed that by the end of the 16th century there were in addition to the Manor House and Hall, 5 mansions3, 22 dwelling houses and 5 cottages. In addition there were at least two soke mills owned by the lord in which it was mandatory for the villagers to have their wheat milled and also a common bakery where it was mandatory for all bread to be baked4.

Footnotes

Sumptuary Laws Laws restricted luxury clothes (or weapons) according to wealth status for both social and economic reasons. The 1463 statute restricted velvet, satin or counterfeit silk to men above the rank of knight and their wives, on the grounds that excess was repugnant to God. Pressures on the social structure from the growing population and distribution of wealth led to 19 proclamations dealing with just clothing in 1516-97 alone.

2 The muster roll for 1534 shows the sum of able men as 31, of which only 5 were equipped with horse. It is noticeable that the names of those who were better equipped, and so better off than the others, figure prominently in the list of tenants who could afford to purchase their tenancies when they were offered for sale in 1604.

3 Mansion — probably a two storied house, of single pile with two cells. One of two bays width. The upper floor being open to the rafters.

Dwelling house — was one and a half stories with one cell of two bays in length and outshot attached.

Cottage – probably of one cell, one and a half to two bays in length, one and a half stories high with outshot.

4 The 1266 Assize for Bread and Malt specified that a King’s officer would be responsible for adjusting the price and number of loaves to be obtained from 8 bushels of wheat. There were allowances of 2.5p for the furnace, 2P for the miller, 2P for the staff, 1p for candles, sacks etc and 3p for himself, his horses, wife, dog and cat. 418 loaves were to be produced from 8 bushels of wheat.

The Manor and Village in the 12th and 13th Centuries

General

In the 12th and 13th Centuries, the Norman manorial system prevailed in England based on the old estates. In effect England was made up of a number of self-supporting manorial kingdoms governed by the Lord of the Manor with its own rules and customs In many cases manors were separated by large tracts of woods, waste lands or even great forests which were by the Crown. The connecting roads, unless of Roman origin, would be grass tracks, deeply rutted by cart wheels or cattle and almost impassable in winter save on foot or horseback. The manors were organised in a relatively straightforward way to suit the period. They were also flexible enough to adapt to the changes of time.

Buildings of a manor would be —

- The Hall and barns, Including a Tithe Barn and other buildings of the Home Farm, the property of the lord.

- The Mill, also usually belonging to the lord, plus a communal bake-house,

- The Church

- The Priest’s house. Not all manors had their own Church.

Small Farmhouses and Cottages with outbuildings that formed the village

The Land – See maps 1,1a and 1b

Outside the village would be the enclosed part of the lord’s farm, possibly one or two detached farms, which did not belong to the lord, and closes for young stock. There would also be remains of farms owned by Danes and/or Anglo Saxons (like Botton and Barras). Although still part of the manor and controlled by the lord they farmed according to their original methods and customs. The characteristic features of the land were very little different from pre-Conquest times.

There were still:

- The open arable fields. In Grassington they were the East, West and Sedber fields, fenced off from the surrounding land

- The Lot Meadows. Land set aside for hay and divided into strips.

- Much larger in size than today, consisting partly of pasturage for stock together with some rough land

- Woods and Wastes. Wood (e.g. Grass Wood, Bastow Wood etc.), moorland, hillside and marshes open to all the village

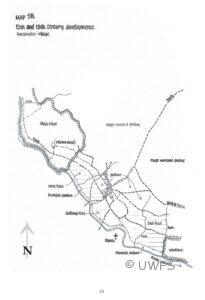

Map 1 Manor prior to 7th Century

Map 1A Angle Settlement

Map 1B 12c and 15c Developments

The Social Organisation of the Village People

The head of the village was the Lord of the Manor. Under Norman law he was considered to be the owner of the land as well as its governor. The lord might be the King, a monastery or some other ecclesiastical institution, a Bishop or some other dignitary. A Norman noble, holding many estates might be the lord or some other layman such as a modest squire holding a few or maybe only one manor. Such manors were rarely bought or sold. If they were in the hands of the Church, they would remain. If a manor belonged to a layman it would pass from father to son, remaining in the family for generations, unless the lord broke some feudal law that would cause the land to be vested in his superior. In this case the manor would be re-granted to a new lord to hold on similar feudal terms as before. The Norman Lord of the Manor of Grassington was Nigel de Plumpton. The de Plumptons were members of the Percy family of great standing with William Conqueror.

The de Plumpton family were Lords of the Manor from 1190 until the Reformation. The Hall was re-built in stone by Robert de Plumpton in the 13th century but was lived in by the lord’s steward – the earliest named occupier being John de Scardborough. Few of the greater lords would, in those days, be found living permanently in the Hall of any particular manor. The lords would visit their estates from time to time, usually in early spring, whilst their main townhouses were being spring cleaned. This enabled them to inspect their property and also to consume the produce from the tithes paid by their tenants. Often the entourage would be quite large so the stewards and bailiffs, together with their families, were evicted to make room for all the visitors.

There were very few freemen living in the manors but these had a privileged position, acting as a barrier between the lord and the lower class farmers and protecting their rights from encroachment by the lord. The freemen usually held their land in return for military or ecclesiastical obligations or, if agricultural, to plough part of the lord’s land. This class of freemen was, by this time, mainly continued in north east England. Most of the farmers were not free but were bondsmen subject to the rule of the lord and his bailiff, but they still clung doggedly to the customs of the past which had not been destroyed by the Conquest.

The Reeve was still the head of the peasants. He was sometimes known as the ‘Provost’ or ‘Praepositus’, titles introduced by the Normans. Below the Reeve was sometimes a ‘Hayward’ who managed the husbandmen. Sometimes there was a ‘Meadsman’ to look after the meadows, a ‘Wood-Reeve’ to manage the woods whilst a ‘Beadle’ collected the rents.

There were two classes of bondsmen. The ‘villeins’ or non-free farmers nominated by the Normans and the ‘cottars’ who held less land than the villeins, an average being a 5 acre strip. Among the peasantry there were men who had special positions in the life of the village — the oxherds, shepherds, swineherds, gooseherds and beeherds. There were also thatchers, ploughmen and ‘ackermen’ or drivers of geese. In a way all these men were officials and worked for both the bondsmen and the lord. They may also have worked for the independent farmers in the manor, if any.

There were also the craftsmen. A community such as this had to be largely self-supporting and could not progress without blacksmiths, weavers and workers able to make the ploughs and carts, agricultural implements, shoes and other leather articles. Some of these craftsmen would be free and some would be slaves. In addition to the men of the community there would have been in some manors, servants of the lord. Some of these might perhaps have been ploughmen, herdsmen, carters etc., who worked only for the lord and some may have been part of the diminishing class of slaves. These servants and slaves would have lived in the precincts of the manorial hall.

Local Government

The village community, the vil, still continued as a public body. In the 13th century major changes in agricultural policies resulted in overworking the land and smaller yields inevitably meant smaller reward. This, together with a large increase in inflation made it more difficult to find the money to pay the rent/tithes to the lord. It was the responsibility of the reeve to ensure that the requirements of the lord were met.

The Hall

This was usually situated on the edge of the village. It consisted, as a rule, of a large hall with one or two smaller rooms. Nearby was the courtyard with a barn for storing corn, a dovecote, farm buildings and possibly accommodation for servants and slaves. With the hall went the Home Farm. The land, possibly of the Anglo-Saxon estate holder, extended and called the demesne. It would consist of a few enclosed strips near the hall intermingled with those of the peasants and subject to the same rules. The possession of these strips would include an entitlement to a share in the low meadows and a proportionate share in the rights over the commons, woods and wastes.

Life in the halls could be rough and simple. The lord’s retainers would camp down in the big hall or in the outbuildings, taking with them rush or straw pallets for sleeping upon. All meals would be taken by everyone in the hall which contained the only fire used for everything, especially for cooking and heating. The lord would reserve for himself and his family, the private room/s, but would join his retainers for his meals. There were no chimneys or flues, the smoke percolated through the roof .

The lord’s main interests would be in affairs outside farm husbandry and he might be expected to spend only a month or two at a time in residence. He came mainly to consume some of the produce stored in the barns, to inspect the bailiff’s accounts and to enjoy some sport in the woods and wastes — such as Grass Wood and Bastow Woods in Grassington Manor .

The Mill

The mill(s) were very important to the villagers and were owned by the lord who claimed the right to grind all the corn and wheat grown and to bake all the wheaten bread. This led to abuse with pricing which gave rise to the ‘Assize of Bread and Malt’ in 1266 which specified by law how many pounds of good bread the baker had to produce for a given weight of flour. In Grassington the mill was sited on the riverside at the bottom of Sedber field.

The Church

Grassington never had its own (Anglican) Church. St Michael’s is the Parish Church of Linton and the first church was almost certainly built by the Norman Thegn, Gamelbar. At some time soon after the Conquest, Grassington was included in the Ancient parish of St Michael and All Angels, together with Threshfield, Hebden and Linton. The Church, however, remained the property of the lord of Linton Manor

The Lords of the Manor

George, the third Earl of Cumberland was the most colourful of all the Cliffords. He was the father of the redoubtable Lady Ann Clifford, Countess of Pembroke. He inherited the Lordship of the Manor of Grassington in 1597 but was little known in Skipton

Whilst deeds of his warlike ancestors were mostly of a military nature, George made his name from naval exploits, where his mathematical skills were put to good use. He took a prominent part in the destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588, the Elizabeth Bonaventure. He was obviously well thought of by the ‘Virgin Queen’. Her Champion at the jousts, he was one of the peers selected to sit in judgement on Mary Queen of the Scots and was created a Knight of the Garter in 1592. At one time one of the wealthiest members of the Elizabethan court, he lost a vast fortune equipping small fleet of ships to raid the Spanish Main as privateers. This venture was singularly unsuccessful. However, he was thought well of by his Queen. It was, of course, to her advantage for George to be successful as a privateer — a buccaneer — as it was her policy to cripple Spain by capturing her treasure galleons sailing from the West Indies and the Americas.

It is said that on return from one of his privateering voyages George had an audience with the Queen. ‘Accidentally’ dropping her glove, George gallantly picked it up and, on his knees, presented it to the Queen who gave it to George to keep. He was so proud that he had it covered in diamonds and, on special occasions, wore it on his hat.

George’s first expedition as a privateer was in 1586, fitting out, at his own cost, three ships and a pinnace. This expedition was a total failure. Altogether George financed eight expeditions of which only one was successful, netting £l50,000, of which George’s share was £30,000. In the process he was severely wounded, suffered intensely from hunger and thirst and was nearly drowned when he fell into the sea whilst in full armour. He captured Puerto Rico but had to give it back to Spain after his forces were decimated by disease.

All this had cost him a fortune and on inheriting the Lordship of Grassington, and other manors, he decided to re-build his family fortunes. His first action was to arrange mortgages with most of his tenants whereby they received a lease of their holdings for a short term in return for a lump sum repayable at a fixed date. However, he made sure that his manorial rights, mineral rights for example, were carefully reserved. Only the tenant lands and buildings were involved. (See Tenants list)

A sum of £909 was raised in this way, not an inconsiderable amount in those days. His next step was to carry out a complete survey to estimate the full value of the manor and this he did by employing a man from Kent called Samuel Peirse. Peirse completed his task in 1603 and it is this survey which shows how the whole township had been used in the preceding centuries. The survey is beautifully written and still survives. It has been used as the basis for this study.

Unfortunately, there is no map to go with the survey and in many cases locations have had to be made as a best guess. See figs. in Chapter “The Sale of the Century“.

The Table (Lists of Tenants and Mortgage Payments made to the Lord of the Manor) shows the names of the purchasers, the ‘freeholders’, how much they paid for the initial mortgage, the total cost of the freehold and the number of yearly instalments paid. It must be remembered that the sale did NOT include the mineral rights — there was lead in them thar hills! — and later the freeholders were to complain that the noxious fumes and lead pollution of their water and grazing was affecting their cattle and sheep

The purchasers, had lived at best in timber framed houses with thatched roofs and walls of mud-and-stud but more often in crude hovels of mud and turf provided by their original landlord. As soon as these new freeholders recovered from the expense of purchasing their tenancies, they began re-building in a more permanent style, using stone, bricks or other available and more suitable materials. In general terms, the rebuilding started in the first quarter of the 17th century and lasted for about 100 years This was because it took several years for the purchasers to recover financially from paying off their mortgages. These new buildings were not shanties; they were robustly built in the Vernacular style of the day and many are still standing. This period, often referred today by modern historians as “The Great Re-Building of England”, was a mixture of revolution and evolution and marked an important watershed in the history of England. It resulted in the tenants being able to own their holdings for the first time and many prospered, becoming yeomen l and husbandmen2.

The medieval long house had only one room with at the best only a wattle screen to separate the family from the beasts. In the north-east of England, one roomed dwellings, often roofed in turf could still be found in the early 20th century Smoke from an open hearth, which was the only source of heat for warmth and cooking, swirled round the rafters.

Many of the monastic estates were sold by the Crown to those lords who supported the actions of Henry VIII, amongst whom can be found the CLIFFORD family. The estates of those members of the nobility who were involved in the rebellion known as the “Rising of the North”3, had their estates attained by the Crown and were executed or exiled. Thus there became available land which could be sold by the lords to their tenant farmers for the very first time. Sometimes the land was sold directly to the tenant, sometimes to trustees representing the tenants and sometimes to speculators.

Henry, Lord Clifford, the eleventh lord of Skipton, was brought up in the Prince of Wales’ circle, which was unfortunate. A reckless man, some said due to the meanness of his father, others think it was due to his jealous mother, he eventually sobered down. Henry married twice: first to the daughter of the fourth Earl of Shrewsbury and second to the daughter of the fifth Earl of Northumberland which enabled the Craven lands of the Percy family to come to the Cliffords. Three years after succeeding to the Lordship of Skipton, he was created Earl of Cumberland. It has been calculated that the cavalcade for the journey to London for his installation as Earl comprised 36 horses. Henry eventually became a Knight of the Garter. During the “Pilgrimage of Grace” Henry held Skipton Castle for the King when all the other northern strongholds had given in. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, as an indirect result of this loyalty, he acquired the Bolton Abbey estates at a ‘very low valuation’

Skipton Castle

Footnotes

- Yeomen — technically those with freehold land worth $2.00 per annum, guaranteeing the right to vote for parliament. Seen as the lowest stratum of society capable of governing, yeomen served as jurors, constables and churchwardens. 1543 Act restricted Bible reading to males of yeoman rank and above.

- Husbandmen — Rarely owned land but farmed holdings of 10-30 acres. Some held 99 year leases, some paid rents which increased at each renewal date.

- “The Rising of the North” aimed to restore Mary, Queen of Scots to the throne and thus restore Roman Catholicism. The Nortons of Rylstone and the Earl of Northumberland, both of whom owned estates in Wharfedale, were involved in this rebellion

“The Sale of the Century”

The Pierse Survey (see Tables 2 and 2a, pages 18 and 19)

The list of tenants at the sale of manor shows a total of 38 houses made up of

- The Hall, Botton and Barras

- 5 Mansions

- 21 Dwellings

- 5 Cottages.

Every survey is described in the same way. In this report the values and rents are converted into today’s ‘units’ but to convert them into today’s values would be unrealistic. The areas are given in four figures eg. -8-2-1-3- refers to acres, roods, dayswork and perches. One dayswork equals one tenth of a rood. Four perches equals one dayswork, ten dayswork equals one rood and four roods equal one acre as today. In tables 2 and 2a the smallest holding is shown for convenience.

The Grassington Freeholders

George Lister resided at The Hall, holding half a hemp plot at Flotter Garth, a meadow called Bickersburg and ‘half’ the mill etc. whilst Francis Clifford held a Mansion house at Botton, half of Grassington Mill, a Barn at the Hall, a field called Maynes Close and the other half of the hemp plot at Flotters Garth

NB Barras and Botton were never considered to be part of Grassington; Botton soon became ruinous and Barras was eventually sold.

The Old Hall is the oldest building in the Manor and is almost certainly built on the site chosen by the Saxon Thegn. It is mainly of 16th-17th century styles with traces of 14th century. The earliest part is similar to Ladywell Cottage (just on the Threshfield side of Grassington Bridge) and other buildings in the dales. The Hall was not lived in by the lord.

In the 1379 Poll Tax the occupant John de Scardeburg was assessed at 17p, the average being a basic 2p (4d)

The Lord did not farm his own demesne, it was divided between his brothers Francis and George Lister. Francis also rented Grassington corn mill with the Lord receiving a fixed profit. Unfortunately the survey does not tell us where the tenants lived but there are good indications to show that almost all of them lived in the area below the Town Hall, with a few in what is now called Chapel Street Each farmstead had its own fold, together with a croft, garden and, usually, a hemp plot. There was much more space than there is today, with the outlying dwellings being few and traffic to and from using high level roads. Barras was important as a much used old enclosure on the moor edge and adjoined an older enclosure but derelict mansion at Botton.

Losskill Bank was so called when William Wrathall was given permission to enclose thirty acres of moor-land above Hebden Gill. He agreed to accept £6.62 from some other tenants but they enclosed 130 acres instead! The house that Wrathall had permission to build was lived in for a long time but the scheming tenants soon lost their enclosure.

| Mortgage acqited | The Sum in the Gross |

1604 | 1605 | 1606 | 1607 | 1608 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49-05-00 | Edmund Wrathall | 220-15-00 | 73-11-08 | 73-11-08 | 73-11-08 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 24-03-04 | Richard Frankland | 95-16-08 | 31-17-08 | 31-18-08 | 31-19-08 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 6-12-06 | The same Frankland | 23-07-06 | 7-15-10 | 7-15-10 | 7-15-10 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 6-12-06 | Robert Wrathall | 23-07-06 | 7-15-10 | 7-15-10 | 7-15-10 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 6-12-06 | William Topham | 23-07-06 | 7-15-10 | 7-15-10 | 7-15-10 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 6-12-06 | William Peart | 23-07-06 | 7-15-10 | 7-15-10 | 7-15-10 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 37-06-08 | Robert Wrathall | 122-13-04 | 40-17-09 | 40-17-09 | 40-17-10 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 26-13-04 | William Topham | 93-06-08 | 31-02-03 | 31-02-03 | 31-02-02 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 33-00-00 | Robert Clark | 127-00-00 | 42-06-08 | 42-06-08 | 42-06-08 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 36-06-08 | William West | 163-1-04 | 54-11-04 | 54-11-00 | 54-11-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 36-13-04 | Francis Hewitt | 123-06-08 | 41-02-08 | 41-02-00 | 41-02-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 30-00-00 | Richard Wrathall | 90-00-00 | 30-00-00 | 30-00-00 | 30-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 24-05-00 | William Wrathall | 95-15-00 | 31-18-04 | 31-18-04 | 31-18-04 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 12-13-04 | John Peart Jnr. | 27-06-08 | 9-02-08 | 9-02-00 | 9-02-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 30-16-08 | Stephen Peart | 129-03-04 | 25-16-08 | 25-16-08 | 25-16-08 | 25-16-08 | 25-16-08 | |||||||

| 23-06-08 | Agnes Williamson | 63-06-08 | 15-06-08 | 15-06-08 | 15-06-08 | 15-06-08 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 27-03-04 | Robert Ibbotson | 90-00-00 | 10-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 21-01-00 | |||||||

| 32-05-00 | William Leyland | 97-15-00 | 21-18-09 | 21-18-09 | 21-18-09 | 31-18-09 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 15-13-04 | John Younge | 64-06-08 | 16-01-08 | 16-01-08 | 16-01-08 | 16-01-08 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 15-06-08 | John Hudson | 64-13-04 | 64-13-04 | 64-13-04 | 64-13-04 | 64-13-04 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 34-13-04 | James Peart | 125-06-08 | 31-06-08 | 31-06-08 | 31-06-08 | 31-06-08 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 35-05-00 | Robert Stockdale | 124-15-00 | 31-03-09 | 31-03-09 | 31-03-09 | 31-03-09 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 45-00-00 | Robert Deane | 115-00-00 | 28-15-00 | 28-15-00 | 28-15-00 | 28-15-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 10-05-00 | Richard Ibbotson | 26-08-04 | 6-12-01 | 6-12-01 | 6-12-01 | 6-12-01 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 41-15-00 | Thomas Peart | 198-05-00 | 39-13-00 | 39-13-00 | 39-13-00 | 39-13-00 | 39-13-00 | |||||||

| 19-06-08 | Robert Wilkinson | 60-13-04 | 12-13-03 | 12-00-00 | 12-00-00 | 12-00-00 | 12-00-00 | |||||||

| 88-00-00 | Robert Oglethorpe | 332-00-00 | 83-00-00 | 83-00-00 | 83-00-00 | 82-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 00-00-00 | William Cooke | 25-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 00-00-00 | George Lister | 900-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 40-15-00 | Geffery Tenent | 193-05-00 | 38-13-00 | 38-13-00 | 38-13-00 | 38-13-00 | 38-13-00 | |||||||

| 27-00-00 | Thomas Leylend | 91-00-00 | 11-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 20-00-00 | |||||||

| 26-06-08 | Roland Peart | 91-13-04 | 11-13-04 | 20-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 20-00-00 | |||||||

| 00-00-00 | The tenants for Botton & Toft | 270-00-00 | 50-00-00 | 50-00-00 | 85-00-00 | 85-00-00 | 00-00-00 | |||||||

| 17-00-00 | Geo. Lister for Cattle Tenement | 55-00-00 | 00-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 20-00-00 | 15-00-00 | 00-00-00 |

Table 1 List of Tenants and Mortgage Payments made to the Lords of the Manor

After the Survey

The account of what happened after the survey is summarised in Table 1.

Column a shows the amount of the short term mortgage, column b. the name of the tenant and column c. the total gross payment. From the table we can see that Stephen Peart had lent the Lord of the Manor £30.85, leaving a balance of £129.15 to complete a total of £160.00 which he paid off by five instalments. His deed shows that he now held the title deeds in ‘fee simple’ for ever. He was now a freeholder with power to sell or bequeath his farm if he wished or to work it in his own way but the lord still held the mineral rights. Stephen still owed suit of court and mill and there was an ‘ancient rent’ to be paid to the lord, a small levy of 2 old pence. This was a relic of the rents that freeholders paid instead of a bonus, often in the form of eggs or hens. These had not been up-dated to account for inflation and no Lord of the Manor of Grassington has been known to demand them since the mill became defunct. BUT the present Lords, the Chatsworth Estates, still hold the mineral rights on Grassington Moor and the new freeholders were beginning to find out their responsibilities and the problems that accompanied them!

4th February 1774

William Brown and 20 others to Sir Anthony Abdy, Bart.

We, whose names are hereunder subscribed freeholders and proprietors of a considerable number of oxgangs of arable land and unenclosed common moores and wastes of Grassington aforesaid, on behalf of ourselves and other freeholders and proprietors of the rest of oxgangs of arable land and unenclosed commons, moores and wastes of Grassington aforesaid humbly beg leave to lay before you as well an exact copy of a grant from the Earl of Cumberland Francis Clifford and Wm. Ingleby & their heirs to one Robt. Wilkinson and his heirs as purchaser of a farm or tenement and one oxgang of land & meadow with the appurtenances situate in Grassington aforesaid and also our grievances which we the said freeholders labour under on account of the said lead ore mines within the manor of Grassington aforesaid.

That the whole three scores oxgangs half an oxgang and the fourth part of an oxgang or arable land, meadow and pasture and the three scores and five oxgangs and half an oxgang of the Common, moore and wastes of Grassington aforesaid have been granted by the aforesaid Earl of Cumberland, Francis Clifford and Wm. Ingilby and their heirs to the aforesaid purchasers and their heirs by indentures bearing date the said second day of May 1604 and contain the same covenants word for word as the annexed copy of a grant to Robert Wiklinson … … by different purchasers.

That a smelting Mill has been lately erected on the out moor of Grassington without the consent of us the said freeholders and which have proved a real Damage to us by our Cattle receiving the injurious particles of the smoke ascending therefrom.

That for time immemorial all the lead ore got within the Manor or Lordship of Grassington aforesaid was smelted with chop wood his Graces property until within this 14 or 15 years last part his graces agent or barmaster at Grassington has dug up and got annually several thousands cart load of turf from off the Commons and moores of Grassington for the purpose of smelting lead ore which if continued will in a few years absolutely consume the Turbary to the great disadvantage of us the said free holders residing within Grassington and also to all other inhabitants of the said Town as burning turf is now and has been our and their chief firing for time immemorial.

Devonshire cannot legally erect smelting mills or cottages houses for the convenience of miners on the Stinted pastures or Commons, Moores or wastes of Grassington, nor can he humbly apprehend dug up turf (which is the sill and trenches) for the purpose of smelting lead ores. That we the freeholders of Grassington also humbly apprehend that his Grace the Duke of Devonshire is liable to be rated towards the maintenance of the Poor in proportion to the Estate and interest he has annually arising within Grassington. The poor rates of Grassington for many years past, and at present run very high on account of lead Miners and their families gaining settlement within Grassington which cannot be avoided.

We the said freeholders humbly beg you’ll take the trouble of perusing the annexed copy of the grant and consider the matter and grievances above stated and return us your thoughts upon the same (when most convenient) directed to Mr. Wm. Brown of Grassington and you will much oblige

Sir, your most obedient servants

Wm Brown

And 20 other names- “

Table 2 Entry no 20 Pierse Survey of Grassington Manor 1603

Table 2 Entry No 2 Pierse survey of Grassington Manor 1603

Table 2a Entry no 20 Pierse Survey of Grassington Manor 1603 – Transcribed

| Robert Smith houldeth one dwelling house with a barn a yard garden & Hemp plot adjoining where unto is also belonginge certaine landes dispersed in the Feilds of Gressington aforesayde the measures & valew hereafter follows |

Redd inde ammatum

4s 4d |

|

| The house, yard, garden and hemp plotte above sayd One medow cloase in the west Feild contayninge One medow parocke amongst the Coave Cloases |

0-1-0-0 6s 8d 0-1-2-1 2/3 2s 2d 0-0-7-1 1/3 |

|

| West Field | ||

| In Sewersill | 0-1-9-1 2/3 0-0-1-3 3/4 0-2-1-0 |

|

| In west Berk lands In the Maynes In bridg Ranes |

0-1-1-0 1/4 0-2-1-1 1/4 0-1-0-2 1/2 |

|

| Sedburr | ||

| In Towne end landes In Kirk landes |

1-3-9-1 0-0-2-3 1/4 |

|

| East Feild | ||

| In the Doates beyond Wyethes Cloases | 1-0-0-0 2s 6d | |

| Summa totalis | 5-3-7-0 2/3 | |

| Whereof medow arable |

1-2-9-3 12s 6d 4-0-7-1 2/3 20s 10d |

|

| In the common pasture 4 beastgates | vat per annum | 20s |

| In the owte Moore ten Sheepgates | vat per annum | 5s |

| Summra totalis valoris per annum supra Redd | 54s | |

| The said Robert Smith hath also one Smythes Fordge standing in the Towne gate For which he payeth |

Yearly | 2s |

West Field : Map based on Peirse’s Survey of 1603: West Field

Map based on Peirse’s Survey of 1603: East Field

Maps based on Peirse’s Survey of 1603

Tenants of the Lord of the Manor of Grassington – 1603

From 1603 Pierse Survey the tenants of the Manor of Grassington are as follows:

| value p/a | ||||

| 1* | FRANCIS CLIFFORD | – House (the Old Hall), a meadow close with field house called Maynes Close, half a hemp plot at Flotter Garth; half of Mill Myerrs, etc | £ 32-8-0 | |

| 2 | FRANCIS CLIFFORD | += one Mansion House called Botton, half of Grassington Mill, etc | £ 12-13-4 | |

| 3 | GEORGE LISTER | = The Manor House called The Hall, half the Hemp Plot at Flotter Garth, a meadow close called Bickersburr and half the Mill, etc | £ 18-10-11 | |

| 4 | ROBERT CLARKE | = one Mansion House etc in the common fields of Grassington two meadow crofts adjoining house, a barn adjoining one of the crofts with a garden, a small garden called Michell garth, one meadow close called Park Style, one meadow among the Cove closes | £ 13-19-10 | |

| 5 | STEPHEN PEART | = One Mansion house with barne, stable, turfhouse, etc | £ 12-2-2 | |

| 6 | JOHN HUDSON | = One Mansion House with barn, yard, garden, and croft adjoining etc. | £ 6-0-0 | |

| 7 | ROBERT DEANE | – One Mansion House with barn and Turf house. A yard, garden, hemp plot and two crofts etc | £ 15-7-4 | |

| 8 | ROBERT STOCKDALE | = One dwelling house with barn and stable together, a yard before the house and a garden with a little croft behind the barn etc. | £ 11-19-4 | |

| 9 | ROBERT WRATHALL | = One dwelling house with barn, turfhouse, two gardens, etc | £ 10-7-1 | |

| 10 | EDMUND WRATHALL | = one Mansion house with barn, two yards, a small paddock behind the house, an oxhouse, a turfhouse with a garden and croft adjoining the oxhouse. | £ 21-13-8 | |

| 11 | JOHN PEART | = One dwelling house with barn and turfhouse, a yard and two hemp plots lying together. | £ 12-4-3 | |

| 12 | WILLIAM WEST | = one dwelling house with barn, two Garden plots with a little lane between them. | £ 14-10-9 | |

| 13 | JEFFERYE TENNENTE & JAMES PEART (the elder) | = one dwelling house with barn, stable & two small garden plots adjoining | £ 16-8-5 | |

| 14 | THOMAS PEART | = One dwelling house with barn, a stable and turf house with two small garden plots | £ 15-13-8 | |

| 15 | JOHN YOUNGE | = One dwelling house with a barne and one garden plot adjoining house and two other small garden plots nearby | £ 6-11-0 | |

| 16 | ROWLAND PEART | = one dwelling house with a barn and two small garden plots adjoining and the said ROWLAND holds one other dwelling house with barn and small plot adjoining said barn. | £ 9-9-1 | |

| 17 | GEORGE IBBOTSSON | = one dwelling house with a barn, garden and hemp plot adjoining | £ 1-19-10 | |

| 18 | THOMAS LEYLAND | = one dwelling house with a barn, a garden, a hemp plot and a little meadow paddock adjoining. | £ 7-10-6 | |

| 19 | JAMES ROBINSON | = one dwelling house, much decayed, with a yard and garden. | £ 7-11-9 | |

| MD At the time of the mortgage, Mr RALPH RADCLIFFE dispursed the whole money for JAMES ROBINSON’S tenement and afterwards the said RALPH conveyed his interest to RICHARD FRANCKLAND, ROBERT WRATHALL, WILLIAM TOPPAN & WILLIAM JOLLY equally betwixt them. | ||||

| 20 | ROBERT SMITH | = one dwelling house with a barn, a yard, garden and hemp plot adjoining. | £ 2-14-0 | |

| MD The said Robert Smith has also one smiths forge standing in the town Gate for which he pays 2s. | ||||

| 21 | RICHARD SETTLE | one dwelling house with a barn, yard and garden, a hemp plot adjoining | £ 4-11-7 | |

| 22 | ROBERT WILKINSON | = one dwelling house with a barn, a yard and a garden & a little meadow croft adjoining. | £ 5-16-0 | |

| 23 | WILLIAM LEYLAND | = one dwelling house with a barn, an oxhouse, a yard, a garden and hemp plot and two small meadow crofts lying together. | £ 8-6-3 1/2 | |

| 24 | JAMES AYRAN | = one dwelling hose with barn and turf house, garden and hemp plot. | £ 2-15-1 | |

| nb; One little strake of meadow lying in a close is in the occupation of JAMES ROBINSON, Wharfe side | ||||

| 25 | ROBERT IBBOTSO N | = one dwelling house with barn, two small gardens and one little meadow croft adjoining. | £ 8-10-9 | |

| 26 | RICHARD WRATHALL | = one dwelling house with barn and turfhouse, a yard garden, hemp plot and one small meadow paddock adjoining’ | £ 9-5-5 | |

| 27 | AGNES WILLIAMSON | = one dwelling house with a barn, a turf house a small garden and a hemp plot | £ 7-0-0 | |

| 28 | RICHARD FRANKLAND | = one dwelling house with new barn, a stable, ox house. yard and garden and hemp plot lying near together. | £ 12-12-2 | |

| memo; JOHN WREATHALL is the old tenant and reserved half for his own but RICHARD FRANKLAND dispursed the money for the mortgage yet has but the other half in his possession. | ||||

| 29 | WILLIAM WREATHALL | = one dwelling house with barn, stable, turf house and one garden adjoining to JOHN WRATHALL his barn. | £ 9-4-3 1/2 | |

| 30 | THOMAS HEWITT | = one dwelling house with barn, stable, turfhouse, garden, hemp plot and a small croft adjoining. | £ 12-9-11 | |

| 31 | WILLIAM TOPPAM | = one dwelling house with barn and stable, a turfhouse, yard, garden and small toft adjoining. | £ 8-10-2 | |

| 32 | SYMON LOFTUS | = one cottage with small garden adjoining flotters garth. | 3/8 | |

| 33 | ALAN IBBOTSON | = One cottage with a garden plot | 4/6 | |

| 34 | WILLIAM IBBOTSON | = a cottage with a small garden | 2/- | |

| 35 | RICHARD FRANKLAND, WILLIAM JOLLYE and ANTHONY WRATHALL | = hold equally betwixt them one new barn and garden plot. | ‘- | |

| 36 | GAWYN HORNER | = one cottage with garden, one stable and cow house (previously a cottage) and small meadow croft. | 6/4 | |

| Memo. Half the rent is paid to the widow Johnson for one of these cottages and the garden. | ||||

| 37 | THOMAS HOLGATE | – One cottage with garden and hemp plot | 5s | |

| 38 | RICHARD IBBOTSON | – One mansion with barn, garden and hemp plot at BAROWES (Barus or Bare House) | £6 6s 1d | |

Building the New House

General

The ‘Great Re-building’1 of a village like Grassington was not quite like that experienced in the larger and more prosperous towns but nevertheless, the rationale was much the same. Although the dwellings were not of the same standard and the roughness of the work of masons and carpenters did not compare with that of the qualified architects, nevertheless, they had an aesthetic aspect that produced a stark but pleasant appearance which has lasted for centuries. However, like the rest of Britain, new houses ‘erupted like mushrooms in the autumn mists’ and an Act was passed 1589 in an attempt to control it by making it illegal to build any cottage which did not stand in a holding of at least 4 acres and to house no more than one family! (It must also be remembered that in Grassington the inhabitants were predominantly peasants who were trying to better themselves and building houses cost money.)

There were no architects; the house design would be a function of the requirement for its use, ie general living, livestock and/or feed storage, field barn, privy, combined animal and living accommodation and the materials available. The building was supervised by stonemasons and carpenters, some of whom would have learned their craft as members of Masonic lodges and craft guilds, previously employed in the building of the many religious houses before the Dissolution. Many of the •new’ were re-builds to improve the comforts of living by bringing the fabric up to modern standards. Although in general terms the most expensive building material is stone, this was in plentiful supply in the northern dales. In Grassington, which lies geologically in rocks belonging to the Yoredale Series in the Carboniferous system, there are many limestone outcrops from which adequate supplies of building stone could be quarried.

Materials

The types of stone required were:

- Rubble — limestone ‘lumps’ that could be roughly dressed for building walls.

- Gritstone or freestone — a hard coarse sandstone which can be dressed and is suitable for the openings in the house, ie doorways and windows and for the quoins at the corners of the walls.

- Stone Flags used for floorings and as roof tiles

- Firestone — a hard sandstone used for fireplaces and ‘backstones’.

- Cobbles — round stones from river beds used for pathways and roads.

In addition to the stone, large amounts of timber were used for roofing and flooring upper rooms. Long lengths were particularly hard to get and were always recycled. Types of timber were oak, elm, mahogany and latterly, pine. Most of the oak came from the oak forest of Barden, but with the continuous wars with France and Spain, long lengths of oak and elm were also in great demand by the Navy for building its ‘Hearts of Oak’ The blacksmith, too, played an important part by the production of nails, door furniture and cooking utensils.

In the Yorkshire Dales there are many different styles and layouts for the new houses but in Grassington nearly all the houses were built to the same style; classified as the ‘lobby-entrance’ it had an upper story, one room deep, the ‘single-pile’ with extra ground floor space provided by an ‘out-shut’ or lean to. The number of ground floor rooms, or ‘cells’, depended on the affluence of the owner. The largest room was the house-body or ‘house-place’ (in Cumbria called the ‘fire-house’) which contained the fireplace on which all the cooking was done as well as, usually, providing the only source of heat

THE CONSTRUCTION

Foundations and Plinths

The foundations were rudimentary compared with today’s standards. It was usually sufficient to roughly level the ground and then cover it with thick flagstones. If the building was sited on a slope, however, a plinth was built, the base of which was slightly wider than the finished building. In Grassington the walls of most houses were built randomly coursed; roughly dressed limestone rubble set in a lime mortar and roughly pointed.

Walls

The walls were made of two layers, an inner and outer with a gap between and tapered off at the top. The space between was filled with the remains of the chippings and the two walls keyed together with through stones; these were sometimes left with the ends protruding. The tops were capped off with thin stone slates acting as water tabling or damp proof course. Dressed gritstone blocks were used as ‘quoins’ laid in the long and short pattern, to interlock the corners of the building and the thickness of the walls of a typical house would be about 90cms at the base tapering to about 60cms at the top. Some of the better quality houses would be built of ashlar, a uniformly dressed stone block which, before the advent of cheap stone-cutting tools, was expensive. Having the advantage of better waterproofing, most chimney stacks were of ashlar. This method of building also made it easy to watershot the courses, the rain being dripped away from the joint and keeping the pointing dry It will be noticed that because of the expense, ashlar and watershot masonry is usually confined to the front of the house only.

The Bay

The size or area of the building was measured in ‘bays’ a term which was derived from the use of ‘crucks’ in timber framed building construction. The feet of a pair of crucks were spaced about 16 feet apart with a distance of about 12 feet from the next, thus forming a cube of 12ft. by 16ft. The Anglo Saxon builders liked this design because it allowed space to turn; in the manors the ox teams were put out to the tenants in pairs to be looked after. Thus by building their tenants cottages to these dimensions they ensured that a house of at least two pairs of crucks would accommodate a family and a pair of oxen. The single bay house was standard for the peasant from Norman times but the cruck method of construction meant that the hovel could at least be improved relatively easily merely by adding another pair of crucks. This system of measurement was used for house plans throughout the Dales right up to the 1 8th century and many families continued to live in single-bay cottages.

The Fireplace

There was usually only one fireplace in the building situated in the ‘Housebody’ — known also as the “house place” and “firehouse”; This was the most popular room in the house; it was always warm, food was prepared and eaten there and there was plenty of gossip to be heard. It was also the best room.

A farmer who had elevated himself to yeoman status would probably build his new house of at least three bays with a layout of three cells; the largest being the housebody, one cell for a (sleeping) chamber on the ground floor and the third cell for a kitchen with larder and stores. The fireplace would have been sited at one end of the housebody, either in the centre or against the dividing wall of the chamber. In smaller houses of two cells the fire would normally have been against the outside wall. Initially there was only one fire used for both cooking and heating which would have had a fire-hood of timber and clay, supported on a wood bressumer beam, through the roof covering. This overcame the problem of smoke from open fires where the smoke was allowed to trickle through the roof covering. In large houses a whole or part of a bay was used solely for the fire — the ‘fire-bay’. Later in the 18th century many of the firehoods/bays would have been replaced by stone arched fireplaces.

17th Century Fireplace

18th Century Fireplace

Windows

Full and efficient use of natural daylight was most important and there was a of interest. Daylight required large openings in the walls which the integrity of the wall in terms of strength and insulation. Glass very costly and made only in small pieces. It was essential to make use of the available daylight so houses were oriented with the front south. The openings were enclosed by gritstone frames and sometimes fitted with vertical bars, mullions, to give strength to a wide window. The openings were splayed to admit the maximum amount of light. The stonework was usually dressed, sometimes to a very high standard. This reflected the Masonic traditions started by the builders of the religious houses before the Dissolution. Some of the stonework was, no doubt, quarried from the ruinous remains!

Rectangular stone mullions

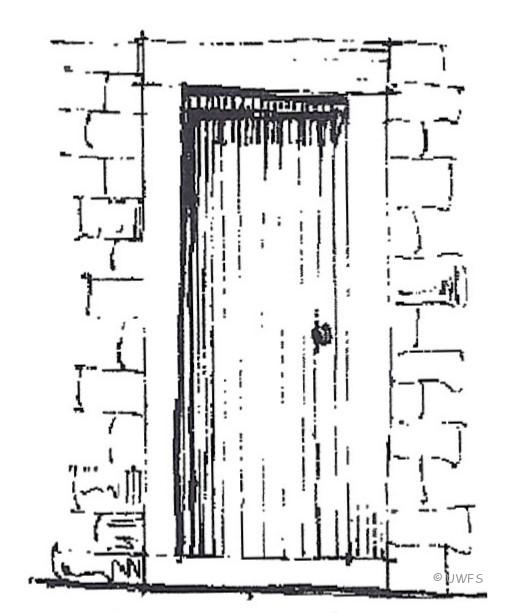

Doorways

Doorways were also stone framed using several matching oblong stones on each set alternately long and short. The front entrances were often decorated with moulded inside edges to the lintels and jambs. Sometimes the lintels would be used to show off the skill of the mason with quite ornate carving which varied regionally Sometimes the date of the building would be shown together with the initials of the builder and his spouse. The jambs, vertical side frames, were made of stones laid in the ‘longs’ and ‘shorts’ method, similar to the wall corner. The doors themselves were made of heavy timber with the door furniture being made by the local blacksmith.

18/19th Century doorway

17th Century door head

In the early stone houses, circular stone newel staircases were commonly built, leading from the ground floor into the roof space. In the smaller single cell cottages it was more usual to have wooden ladders fixed to the wall or perhaps a steep flight of stone stairs which could be enclosed with a door where the roof space was used for sleeping.

Roofs

Most medieval Dales buildings would have been thatched with Ling but there is little evidence of its widespread use during the rebuilding of Grassington, where stone slates or flags appear to have been used almost exclusively. There being no timber frame with the new house, roof timbers were built directly into the stonework. There were many forms, the simplest using roof trusses secured to the outside walls with rafters held together at the apex by a ridge pole. Purlins were laid across the principle rafters supporting the common rafters which in turn supported the laths holding the stone slates. The style of roof selected with any particular building depends on its size and sophistication. Curved wind braces were frequently used with complicated church roofs. The external ridge was usually covered with ridgestones and the gable ends with water tabling, supported at the walls by stone kneelers.

Chimneys

In Grassington, fireplaces in three-cell houses were normally sited towards the centre of the room with the flue built into the dividing wall. In two cell houses it would be sited against the outside wall with the flue contained in the gable end wall. Whilst it is common in some parts of the Pennine Dales to find the fireplace and its flue with stack on the outside wall, it is rarely seen in the Yorkshire Dales. The chimneys were built either of ashlar block or sections of thick stone flag, it being essential to use fire resistant stone that could be closely bonded to prevent leaks. The stacks were usually decorated with moulding towards the top with a stepped base sitting astride the ridge and damp-proofed with lead flashing (procured from the lead mines on Grassington Moor).

Footnote

1 – Great Re-building’ a movement identified by Professor WG Hoskins and dated to the period 1570-1640 in southern England. In Yorkshire the period is a little later

Common Surnames in Late 16th/early 17th Centuries in Parish of Linton in Craven

From Parish Registers 1562 — 1812

| Surname | Derivatives | Tenants |

|---|---|---|

| Airey | Aerey, Aerie, Airah, Airay, Aray, Areah, Arie, Ayeray, Ayray, Ayrey. | |

| Ackroyd | Akeroid, Acrode, Aecroide | |

| Atkinson | Atkinsonn, Attkinson | |

| Ayrton | Aareton, Aerton, Aertone, Aertoun, Airton, Ayarton, Ayerton, Ayreton | |

| Batty | Battie, Battye | |

| Baynes | Baine, Baines, Bains, Bay.., Bayn, Bayne, Bayns | |

| Blackburn | Blagburn, Blagburne, Blaggburn | |

| Bland | Bland, Blande | |

| Brayshaw | Braishay, Brayshay, Brasha, Brashaw, Brayshey, Breshaw | |

| Brown | Bron, Broun, Browne | |

| Clarke | Clarck, Clark | *Robert Clark |

| Cook | Cooke | *William Cooke |

| Darwin | Darran, Darwan, Darwand, Darwen, Darwend, Darwent, Darwente, Darwon | |

| Dean | Deane, Dene | *Robert Deane |

| Fletcher | ||

| Fountaine | Fountain, Fountaines, Fountains, Funtaine, Funtainers | |

| Frankland | Franckland | *Richard Frankland |

| Hudson | *John Hudson | |

| Hewitt | Hewett, Huett, Hueit, Huit | *Frances Hewitt |

| Ibbotson | Ifitson, Ibotsonn, Ibbinson, Ibbitson, Ibboson | *Robert Ibbotson |

| Inman | ||

| Kidd | Kid, Kidde | |

| Kitching | Citchen, Kitchen, Kichin, Kitchinge, Kitching | |

| Lambert | Lambard, Lambte, Lambtre | |

| Leyland | Layland, Leland, Laylande | *William Leyland, *Thomas Leyland |

| **George Lister | ||

| Lupton | Luptonn | |

| **Robert Oglethorpe | ||

| Peart | Pearte | *William Peart *John Peart Jnr. *Stephen Pearte, *James Peart *Roland Peart |

| Radclyffe | Radcliffe | |

| Rathmell | Rathmel, Rathmill, Wrathmill | |

| Robinson | Robbinson, Robinsonn | |

| Sainforth | ||

| Stockdale | Stocdaile, Stockdaile, Stocdall, Stockdail, Stoctal | *Robert Stockdale |

| Tempest | Tempeas, Tempes, Tempeste | |

| Tennant | Tenant, Tenante, Tenente | *Geoffrey Tenent |

| Thompson | Thomson, Tompson, Thomso, Tomsonn | |

| Thopham | Thopan, Thopphan, Topan, Tophan, Tophann, Tophhan | *William Topham |

| Wellocck | Vellock, Wallock, Wallocke, Walloct, Wellecke, Willacke | |

| West | Weste | *William West |

| Wilkinson | Wilckingson, Wilkingson | *Robert Wilkinson |

| Williamson | Williamson, Wmson | *Agnes Williamson |

| Wrathall | Rothall, Waythall, Wrathal, Wrathel, Wrathoe, Wrathoo, Wrathow, Wraythall, Wreathen, Wreathey, Wrethall | *Edmond Wrathall, *Robert Wrathall, *Richard Wrathall |

| Young | Yong, Yonge, Yonnge, Younge | *John Younge |

*Robert Clark and others so designated are Freeholders listed in Parish Registers in 1604

**George Lister and Robert Oglethorpe do not appear in Parish Register in 1604

Acknowledgements

Susan Brooks MA, Historian – whose books on local history engendered in me an interest in Vernacular buildings.

J.K.Lockyer B.Ch.D(Univ of Leeds) L.D.S – who researched the purchase of freeholds on Grassington Moor by the first freeholders regarding mineral rights between freeholders and the lord of the manor.

Margaret Lockyer – who readily made available documents for my perusal.

Dr. R.T.Spence, Historian – who made available information gained whilst researching the Chatsworth archives regarding the Pierse Report.

Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement.

Brian Moxham – my patient and helpful friend, who as leader of the Vernacular Building Study Group has co-operated and helped with collating all the material. Brian also coped with a major difficulty when much of the original data was lost in my computer.

Pam Wilkinson.

Colin Wilkinson.

Ian Goldthorpe.

Alan Akers – who valiantly typed the Pierse Survey.

Dr. David Turner and members of the Geology Group.

Edwin and Wendy Page – Proofreaders.

Anne Sugden who has typed, printed and bound the final manuscript, patiently coping with delays in the layout and script.

and to those members of the Vernacular Buildings Study Group who have helped in any way with compiling and producing this work by practical means or encouragement.

February 2006